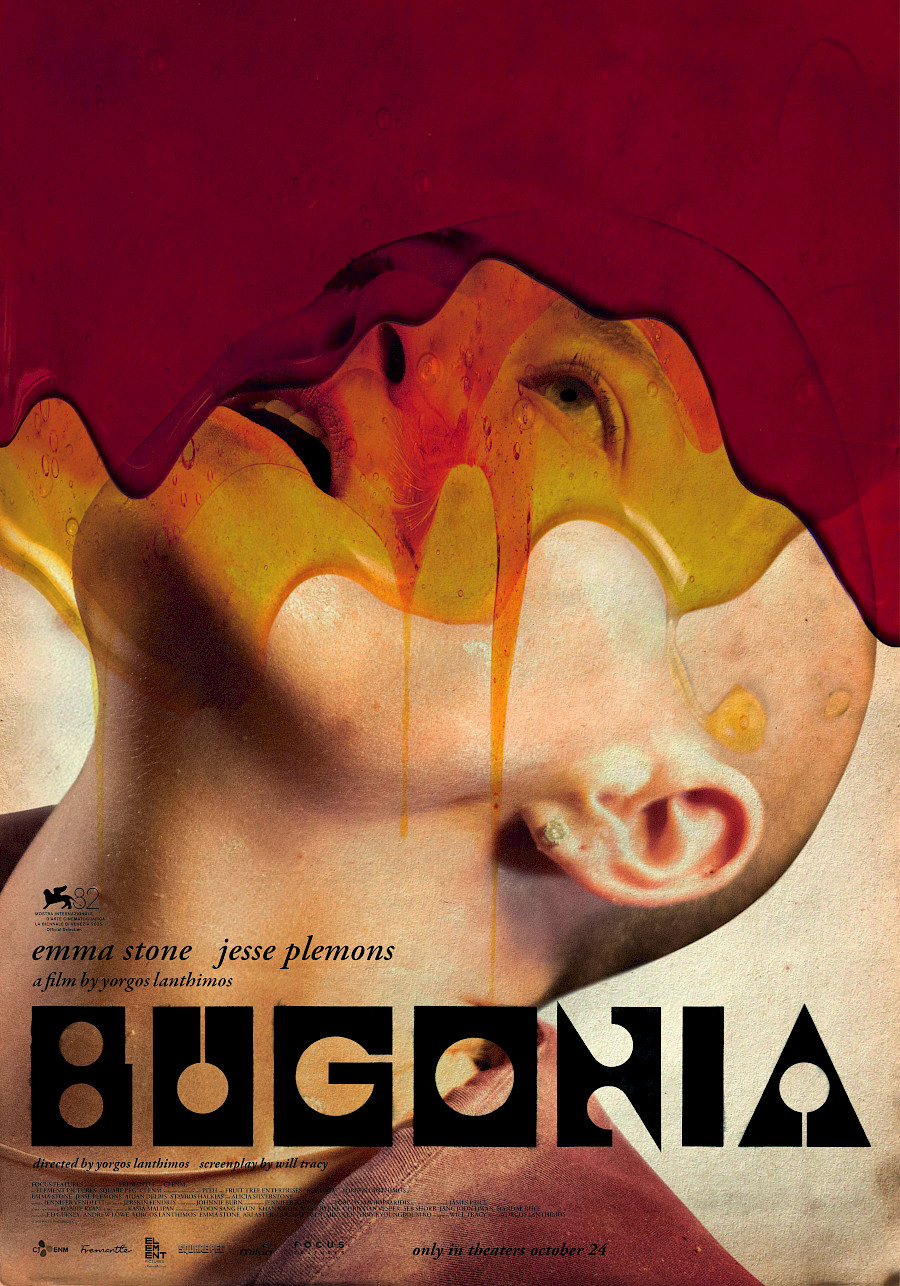

Another Yorgos Lanthimos masterpiece is returning to theatres

One of the boldest and most influential filmmakers of our time, Yorgos Lanthimos is known as a master of paradox and provocation, cold irony and eccentric aesthetics, fearless experiments with human nature and insanity. His path started in Athens, but quickly transcended national cinema, turning his name into a synonym for a new cinematic revolution. Each of his films is an invitation to a universe where beauty coexists with cruelty, and laughter becomes a mirror of our deepest fears and desires. His first international triumph came with Dogtooth. With The Lobster, he proved that absurdity can be as romantic as it is tragic, and with The Favourite, he conquered Hollywood once and for all. A few years ago, Lanthimos’s Poor Things was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. This year, he returned to the same stage with a brand-new film, Bugonia – the main focus of his conversation with NARGIS Magazine.

Emma simply said, “You know what, I’ll shave my head for the role. But you’ll have to do it too, in solidarity”

I love taking pictures, sometimes more than film

Emma and I have developed an extraordinary working relationship

The title of your new film carries a mysterious word – “Bugonia.” What does it mean, and why did you choose it

Bugonia refers to an ancient Greek belief of “spontaneous generation.” The film highlights the absurd yet stubborn nature of the characters’ actions. I wanted to show how, in today’s world, people live inside their own bubbles. Technology has only thickened these walls, shaping our perceptions of others depending on the bubble we find ourselves in. I wanted to challenge these stereotypes and provoke the audience: how confidently do you judge others, and how well-founded are those judgments? It’s my way of reflecting the contradictions of our society and the conflicts we are going through. And while the film can certainly be called a comedy, it is far more layered and textured than it first appears, leading the audience into places they never expected to go.

Absurdity runs through every layer of life

What inspired you to tell this story?

It all started with Will Tracy’s daring and witty script. A few years ago, the film’s producer, Ari Aster, suggested Tracy watch the Korean film Save the Green Planet. He had never heard of it before, managed to track down a copy, and that was the spark for his own story. At the time, we were all confined to our homes

during COVID, slowly going mad in enclosed spaces. In his small Brooklyn apartment, Tracy wrote the script in just three weeks – without overanalysing, simply capturing that overwhelming sense of claustrophobia shared by millions. When I got the script, I immediately recognised in it the blueprint for a darkly comic provocation: a new kind of psychological thriller, made for the big screen – and for the absurdity of our times. Reading it was effortless. It was engaging, layered, and felt incredibly relevant.

I instantly wanted to see it in a cinema – to laugh, to cry, to groan, to recoil alongside other people. Most films are meant to be experienced that way: in a theatre, with an audience. It’s a rich, dramatic encounter, in both humour and horror, and one that

can only be fully lived on the big screen.

Your film feels like an incredibly precise reflection of today’s reality. What mattered most to you in this story?

This film truly captures our present-day world and the disconnection from reality that fuels so many divisions among people. I first read the script about three years ago, and unfortunately, it feels even more relevant today. We see how wealth, fame, and success can change people, making them less empathetic. Despite having endless means of communication, we’ve forgotten how to truly communicate. We no longer listen, no longer understand one another. Technology was supposed to elevate us, yet more often it seems to drag us backwards, leaving us more primitive. Social media has replaced the news. It shapes our perception of the world as if everything happening is somehow outside – beyond us, unrelated to us. We think we see and know everything around us, but in truth, perhaps never before have we known so little. At the same time, it feels as if we’re losing the very ability to control anything. It might appear that the film is built as a dystopia, but I don’t see it as a fictional warning about the future. On the contrary, many of its absurd details are direct reflections of today’s reality. For me, it is not a dystopia, but a mirror of our time. And precisely because of that, humanity will soon face a choice – to take the right path. Otherwise, I’m not sure how much time we have left, given everything happening in the world: technology, artificial intelligence, wars, climate change, and our astonishing indifference to these threats. For me, above all, this film is about the present. And I hope it prompts viewers to think about what is really happening around us.

This is your fifth collaboration with Emma Stone. What is the secret behind this creative bond?

Emma and I have developed an extraordinary working relationship. She is not only an actress but also a producer, often surrounded by the same people we’ve worked with from film to film. It feels almost like a family: we take on quite complex projects, yet we always feel safe and supported, working in an atmosphere of trust. That’s rare and almost impossible to recreate. Emma and I share similar tastes and a common vision for the material, so it was no surprise that she immediately saw in this story what I did – a funny yet frightening mirror of our times. I sent her the script right after reading it, because I trust her intuition. I gave her the freedom to discover Michelle’s character on her own. That journey led her to shave her head completely. At first, we considered to fake it, but it quickly became clear that the process would take far too long. Emma simply said, “You know what, I’ll shave my head for the role. But you’ll have to do it too, in solidarity.” And that’s exactly what we did. I shaved mine first, then hers, and from then on, we had to repeat it every couple of

days. Oddly enough, it turned out to be very convenient as our morning prep for shooting was suddenly much quicker.

How did you work with sets and costumes to create the film’s absurd reality?

The house where most of the action takes place was built entirely from scratch. We created a fully immersive environment just outside a grand country estate in London, in a small valley. We built not only the external façade, as is usually done, but the entire exterior and interior at once in one place. It was so convincing that the actors and crew often forgot they were in the English countryside, and not on a dilapidated ranch somewhere deep in rural America. As for the costumes, I wanted them to align

with recognisable archetypes: “the authoritarian CEO,” “the guy who scans parcels,” or “the one who spends all day playing video games.” Michelle Fuller, the CEO, embodies this perfectly – dressed in a black Alexander McQueen suit, a white shirt,

Louboutin shoes, and a Saint Laurent bag. It’s the quintessential corporate leader look. People like her don’t really have personal style or individuality; it’s as if they all wear the same uniform.

Why do you enjoy sarcasm and dark humour so much?

Without humour, stories lose their essence. How can one take life too seriously when the world around us is full of absurdity? I get irritated by people who take themselves too seriously. It’s essential to laugh at yourself and see the comic sides of existence. This doesn’t mean abandoning respect for authority, avoiding responsibility, or working carelessly. But if you live as though every single moment is solemn and monumental, you narrow your perception of the world. Even in the deepest tragedies, there is always something comical, something ridiculous. For me, keeping distance and looking at things from different perspectives is crucial – this is when you realise that absurdity runs through every layer of life.

Actors who worked with you have said that rehearsals with you are unusual: they had to roll on the floor, throw themselves at one another, and repeat strange lines. Is that true?

I don’t want to publicly reveal my working methods. What I can say is that I love observing people in awkward situations, when they feel uncomfortable and exposed. I believe it’s important to push actors out of their comfort zones by every means possible. I enjoy watching them act silly, even foolish. I prefer those moments when actors don’t fully understand what they’re doing and have to rely on instinct. At first, they feel insecure, even vulnerable – but with time, they grow freer. If they can handle such moments with dignity, it leaves no doubt about their talent. I’m always curious to challenge human relationships and explore human behaviour. Experiments in rehearsals can lead to surprising outcomes. At the same time, I try to leave enough space for the audience’s imagination, without spelling out the meaning or falling into a moralising tone. It’s important for me that the viewer continues thinking after the film ends.

- Yorgos Lanthimos studied business and played basketball before attending the Hellenic Cinema and Television School Stavrakos for directing.

- He is influenced by writers like Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Beckett.

- In March 2025, Lanthimos had a debut exhibition of still photography at the Webber Gallery in Los Angeles.

- One of the recurring themes in Lanthimos’s films is the difficulty of human connection.

- Lanthimos avoids explaining the meaning of his films as he believes that viewers should interpret the work themselves.

- He was a member of the creative team for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies for the Athens 2004 Olympic Games.

When did your passion for storytelling begin?

Since childhood, I spent entire days glued to the TV, watching all the movies out there. I can’t recall exactly what first made me want to direct my own films – perhaps it was simply instinct. Or maybe I wasn’t particularly fond of the reality around me and preferred to escape into an imaginary world, and build that world myself. Even today, when I make films, I still feel closer to fantasy than to so- called objective reality, which, in truth, is never objective at all.