It is believed that an untold story does not exist. Everything has already been written and filmed, but this doesn’t stop curious minds from searching for new visual forms for old stories. Thus, the language of cinema is created. Each country has its own distinct cinematic language. For instance, films by Asian directors are often minimalist, have a slow pace, and are concise. European films usually tackle pressing social issues, contrasting with American filmmaking, where spectacle takes priority. Although the examples here are generalised, one can still conclude that the audience is different everywhere, and the language of cinema is shaped by the mindset and psychology of each nation. In a sense, this is where the magic of cinema lies. Like a person, language evolves over time, and this process is irreversible, as the economy grows, science and technology develop, and the pace of information transfer from point A to point B increases, ensuring rapid growth and change. However, not everywhere are these changes ready to be embraced with open arms, especially in “In a Southern City” by Eldar Kuliyev, based on the short story “9 Khrebtovi” by Rustam Ibrahimbekov.

In 1969, a film was released on the big screens of Soviet Azerbaijan that changed the perception of cinema in the country. Soviet films often dealt with the themes of World War II, as the victory over fascism was seen as an example of perseverance, honour, and valour for the Soviet people, or they adapted stories from the lives of ordinary working people. Naturally, there were also experimental films, but there was no neorealism in Azerbaijani cinema until Eldar Kuliyev, and it was not openly supported by the government. The reason at first seemed very simple, but upon closer examination, it became clear that things were not so straightforward.

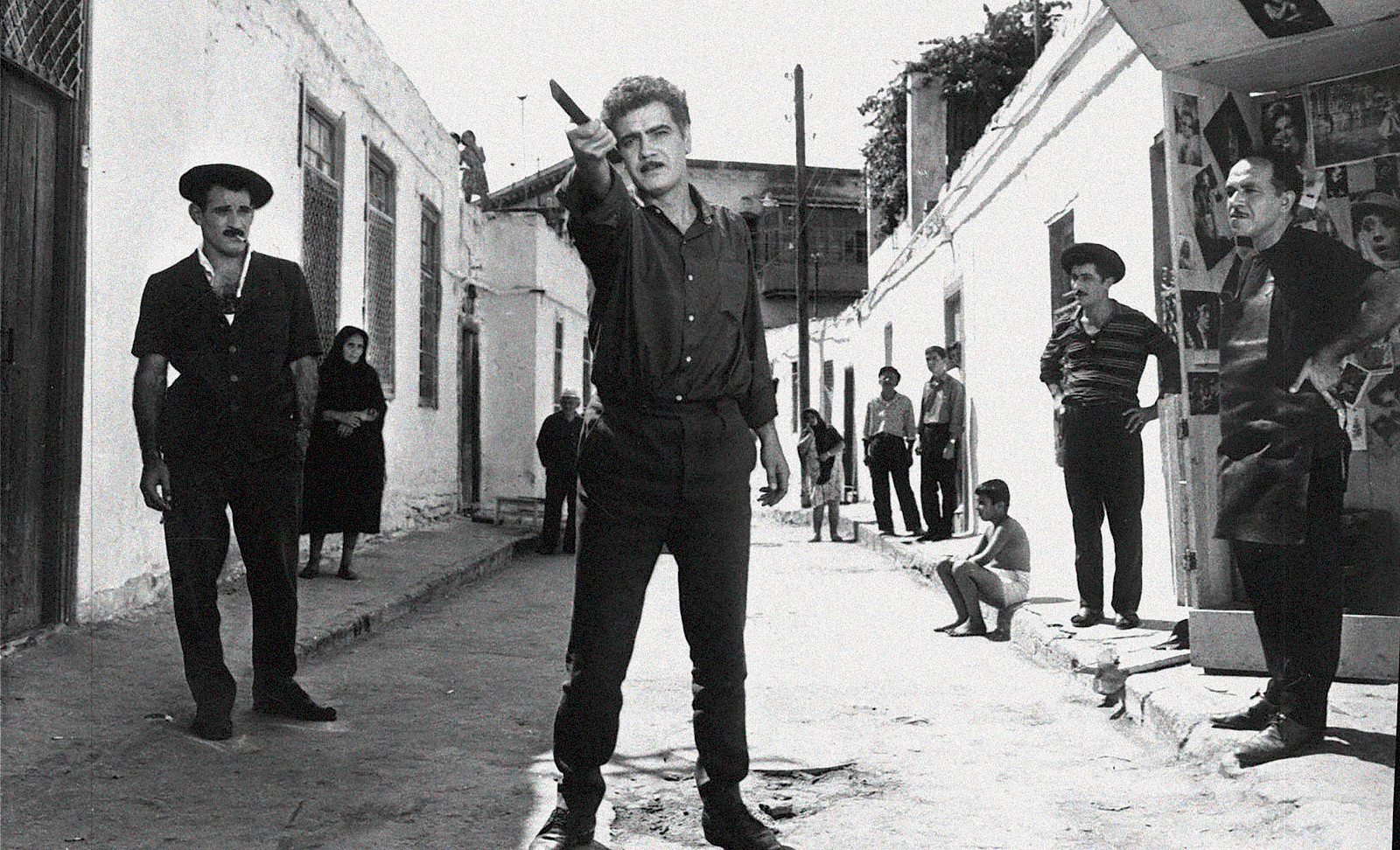

The story takes place in a fictional southern city. From the first scene, it becomes clear that the young woman, who has found a job at the local street-side grocery stand, has problems with her husband. The very fact that his wife works for another man is unacceptable, and rumours circulate around the neighbourhood that soon, according to unwritten laws, the husband will come for the stand’s owner. And so, it happens. The husband arrives with a metal pipe in hand, and with one strike, he takes the life of the small businessman. The entire neighbourhood, from the smallest child to the oldest adult, watches the event, and no one, following those same unwritten laws, intervenes. Even the local officer does not attempt to intervene but instead waits for the moment when the conflict reaches its natural conclusion, and the criminal quietly and calmly walks with him to the police station, from where he will honourably serve his time in prison. Suddenly, an ambulance appears at the crime scene, from which medics emerge and with steady steps, load the deceased into the vehicle and drive away. Behind the ambulance, a mentally disabled person runs, imitating the sound of the car, symbolising the deceased’s transition to the eternal world. In the next scene, a boy, holding a jug of water in his left hand, scrubs the bloodstain on the asphalt with a broom in his right hand. The blood mixes with the water and flows along the asphalt until it reaches the first crack, where it is absorbed by the soil, nourishing it and strengthening the social fabric of the narrow streets with their white walls. While this may seem barbaric to a modern viewer, to those familiar with Southern traditions, it makes perfect sense. The protagonist, Murad faces a dilemma between his heart’s desires and society’s demands. His choice remains unknown, even to him, but this dilemma signals the arrival of progress that rethinks traditions rather than rejects them. This process will lead to the evolution of values; otherwise, these norms will become so outdated that future generations will no longer follow them. At that time, only a few individuals confronted such dilemmas during the early stages of cultural blending. As a minority, they often faced conflicts so intense that crime seemed like the only solution. To make the right choice, one needs time to see alternative solutions beyond simple understanding. Murad is a victim because he must fight for his love, and at the same time, he is a trailblazer, as he must kill his friend Tofig to protect his family’s honour. However, deep inside, he is tormented by the fact that he is forced to commit a crime. Even though the sincerity and boldness of Eldar Kuliyev’s film “In a Southern City“ were revolutionary for Azerbaijani cinema and sparked an ambiguous reaction from both the government and the audience – many of whom believed that it tarnished the reputation of the Azerbaijani people – the film ultimately became iconic. This was because it openly depicted the consequences of the blending of contradictory ideas from different cultures, which motivated progressive thinkers within society to fight against the distorted exploitation of the logic of traditions, which, when interpreted correctly, are wise and multifaceted. It can be confidently stated that the formation of traditions is closely linked to the ideas born from human reactions to what is happening, whether consciously or not. In other words, traditions are a time machine that can only travel in one direction – to the past. No matter how insignificant the past may seem in the present, it is the foundation of what exists now. Modern worldview suggests not holding onto the past, because by trying to hold onto something that is by nature changeable, tension is created, which is reflected in a person’s thoughts and actions. But it is this tension that leads to struggle, giving birth to heroes and revealing the inner genius of Azerbaijani thinkers.

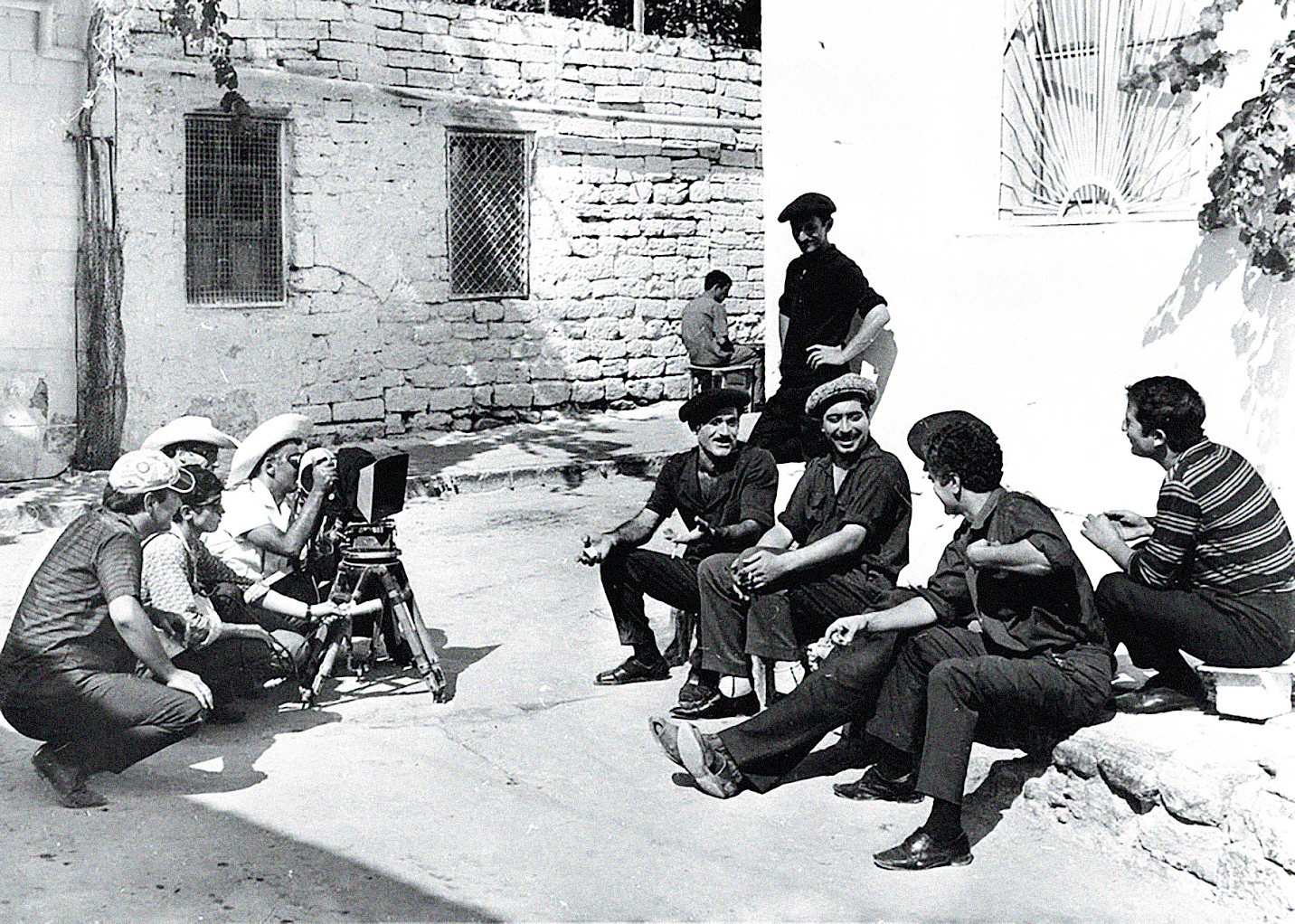

We painted all the walls on the street where we filmed the movie white.

Rasim Ojagov, director of photography of the film «In a Southern City»